The complete history of the three Seaford cinemas. From the basic cinema in Brooklyn Road. The purpose built cinema in Sutton Road, and the magnificent, suitably named, Ritz Cinema in Dane Road.

I am indebted to Charlie Grimble for his help with the story behind the Brooklyn Road theatre.

The histories of the Empire and the Ritz cinema’s have been compiled from an in depth article in the ‘Picture House’ magazine printed many years ago in the 1980’s, and written by John Fernee, with the help of Mrs. June Howard’s (nee Langdon) reminiscences. Our local newspaper, the Sussex Express reported on the Empire fire.

The photos are credited to Picture House, Seaford Museum, Jim Marsh and Seaford Times.

CHAPTER ONE.

BROOKLYN ROAD PICTURE THEATRE.

Researched and written by Charlie Grimble.

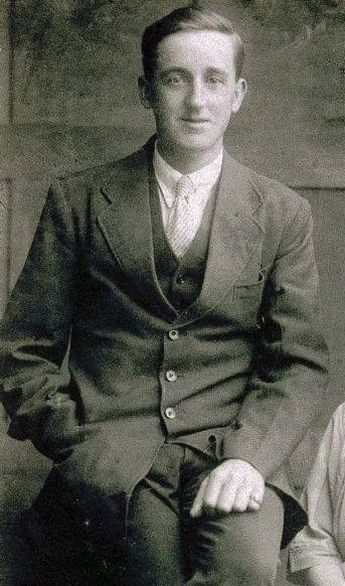

Thomas Funnell, (b.28/3/1868 Hellingly, d.4/3/1955, Green Woodpecker, Kammond

Avenue, Seaford) wife Ellen Georgina Funnell (nee Hance),born 2 May 1871 at Hill Head, west of Gosport, Hampshire, died 4 April 1957 Taunton, Somerset.

Thomas was a builder and carpenter who moved into a Lodging House, Gosport House, 14, The Esplanade, Seaford in 1901 and remained in Seaford for the rest of his life.

He bought the land at 48 Brooklyn Road, on 10 April 1905. He built a workshop in 1908 probably in anticipation of a sale to Seaford Gas Company who, on 23 November 1906 had sought approval from the Board of Trade (published in the London Gazette on that date) to acquire land surrounding the Gasworks site (including Thomas Funnell’s land).

However, although the gasworks were extended at that time, it was not necessary to purchase No 48 Brooklyn Road. Thomas Funnell therefore had to find some interim use for his building and so he changed it in late 1909 to a roller skating rink, and occasionally films were shown there.

It was lit by gas, as electricity had not come to Seaford at that time. Roller Skating rinks on a commercial basis first appeared in the UK in 1857 with one in The Strand, and also in the Floral Hall, London, swiftly followed by 48 more by the 1870’s, using the recently new design of the quad skate (previous types were in-line skates), It died down again but briefly re-erupted in in 1909 when 38 companies registered in the UK.

On 12 May 1911 in the name of his wife Ellen Georgina Funnell, Thomas Funnell bought from the Seaford West Company, the adjacent plot now occupied by the building used by Swindells, probably to make the whole entity more attractive for onward sale to the Gas Company. The building did not last long in that form as Charles Bravery built The Empire Cinema in Sutton Road in 1913 and that cinema thrived. Pike’s Blue Book of 1910-11 calls Funnell’s building ‘a skating rink and concert hall’.

Thomas Funnell bought the Martello Tower in 1911 and got approval for converting it into a skating rink on 12 August 1912 (The Keep Ref DL/A/34/372). In the works to adapt the building for commercial purposes, he included a skating rink and tea rooms. Pike’s Blue Book of 1912-13 has the Electric Picture Theatre adjacent to 44 Brooklyn Road. This description has disappeared by the time the 1915-16 Pike’s Blue Book was compiled.

The Brooklyn Road building today. (2020)

(Charlie Grimble)

CHAPTER TWO

THE COMPLETE HISTORY OF THE EMPIRE CINEMA.

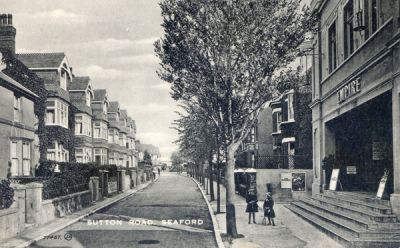

(This Valentine postcard courtesy of the Jim Marsh collection)

On 22nd February 1913 Mr. Charles J. Bravery, Mr. H. Ediss and Mr. F. Ediss, with a capital of £3,000 in £1 shares, registered a company for the purpose of erecting an ‘electric or cinematograph theatre’. They called the company ‘Seaford Empire Company Limited’. The company was registered by Crawford & Barwell, solicitors, Seaford.

The number of directors of the private company was to be not less than two, and no more than three. The first directors were Bravery, Ediss and Ediss.

Regardless of this within seven months Mr. C. J. Bravery was in sole charge of the company, and spent just under £2,000 having the 72ft x 32ft theatre built by local builder Mr Wilkinson, on a plot of land in Sutton Road, already owned by Mr. Bravery.

Charles J. Bravery was a property owner and estate agent, whose business interests were supervised by his son, C. Victor Bravery, of Blatchington Estates, Station Road, Seaford. The Braverys did not operate the Empire themselves, but leased the cinema out.

The Empire was a 500 seater cinema, completed in 1913. Sutton Road at the time was residential. Houses had been built on both sides of the road, all with small gardens leading to the front door of the building. To build the Empire in keeping with the houses, the steps leading to the entrance of the cinema took up the the depth of the gardens, which allowed the front of the cinema to be built near enough in line with the houses.

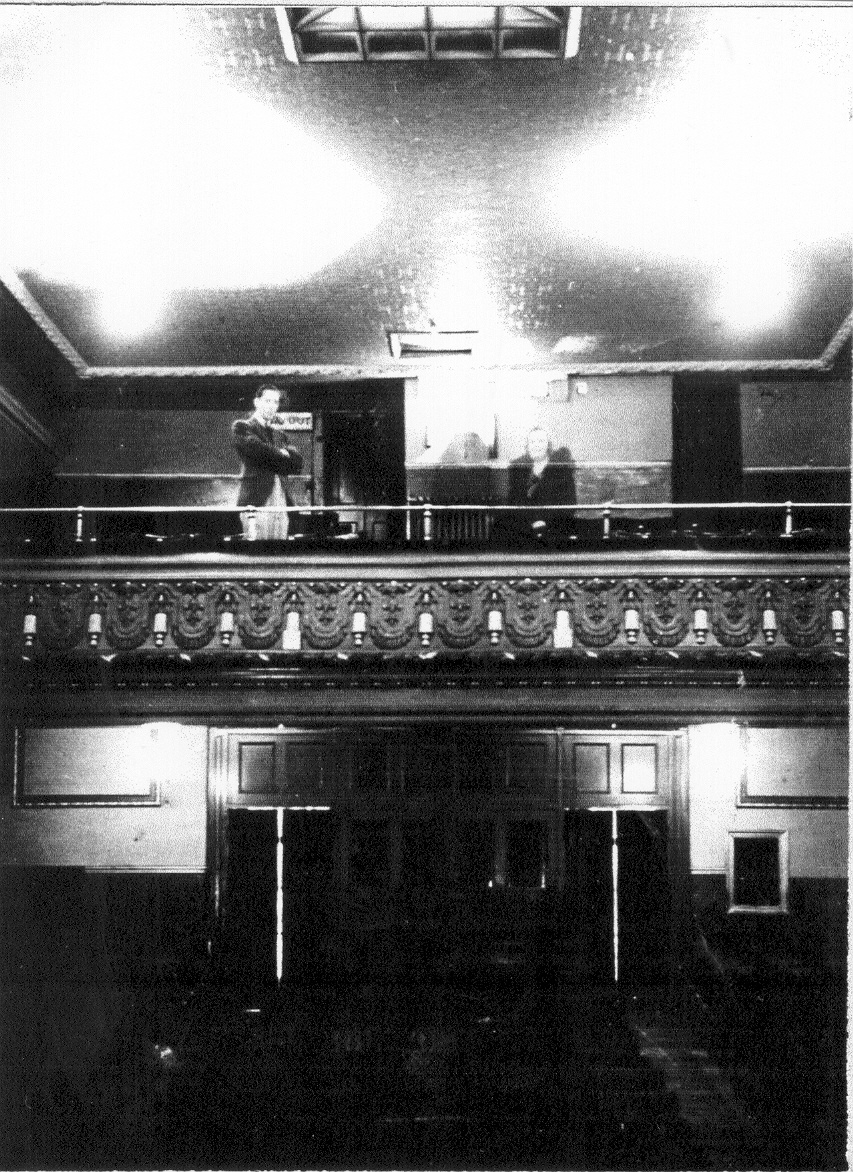

On entering the front foyer of the Empire, the kiosk was right in the middle. There were two swing doors leading to the inner foyer, which had a large radiator. On winter evenings many of the staff would gather around this radiator for extra warmth.

Further in there were another two swing doors leading you to the auditorium. The auditorium was very well furnished. The balcony was decorated in plaster motif’s and the ceiling lights were of a dome shape.

By all accounts the Empire was a very popular cinema with Seaford folk, especially the courting couples, as it had an atmosphere about it that many people liked.

(Empire interior. Photo Seaford Times files)

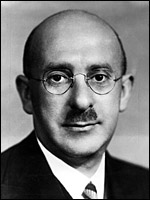

Oscar Deutsch

In 1932 the lessees were Cinema Services (Birmingham) Ltd., which was the name that Oscar Deutsch traded under.

Oscar Deutsch was born in Birmingham in 1893. His father was a Hungarian emigrant who had prospered in scrap metal. How, and when, it was that his company first became the lessee of the Empire is unknown, because by the 1930’s he was heavily involved in finding sites in towns all around the country for prospective businessmen to build his Odeon cinema’s. His first cinema was built in 1928, but not called Odeon. The first named Odeon was located in Perry Barr, Birmingham. By 1933 he had 26 Odeon cinema’s, alleged to be an acronym of ‘Oscar Deutsch Entertains Our Nation’, and by 1937 there were 250, with the Leicester Square Odeon the flagship.

Deutsch eventually sold his chain of cinemas in 1938 to J. Arthur Rank, who was in the process of forming the Rank Organisation. By the time of Oscar Deutsch’s death in 1941, 258 Odeon had opened throughout Britain.

(Brian McFarlane, Encyclopaedia of British Cinema & Wikipedia)

Living in London at that time were Mr and Mrs. Lloyd Langdon. Mr. Langdon was general manager of Sir Oswald Stall’s theatres. He had supervised the change of the Stoll Theatre in Kingsway, London to the Stoll Picture Theatre. Suffering from asthma, he was advised by his doctor to move to the South Coast.

In 1931 he and Mrs. Langdon moved to Seaford and decided to go into the cinema business, purchasing the lease of the Empire from Oscar Deutsch.

This suited both parties. Oscar Deautsch would no longer be committed to running the Empire, giving him more time with his venture of acquiring land in suitable towns for building Odeon cinemas for local businessmen.

Whether or not it was during the time Deutsch operated out of Seaford that he examined the possible trading position for new theatres in other South Coast towns is open to conjecture. Certainly the early Odeon circuit was strongly represented in the south with new cinemas at Bognor, Kemptown, Lancing, Lewes, Littlehampton, Portslade (the Rothbury), and Worthing

As for the Langdon’s, they were back in the business of managing a local cinema, which they had been so successful in London.

Unfortunately, Mr. Langdon passed away within three months of their move to Seaford, and therefore Mrs. Isobel Merriman Langdon became the sole leaseholder.

Soon after, while Deutsch early Odeons were under construction at Lancing, Portslade and Worthing, a hoarding was erected on the site of what was to become the Ritz, saying that a new Odeon theatre would shortly be built there. This caused great alarm to Victor Bravery, who could see that the viability of his Empire Cinema would be affected, and also to Mrs. Langdon.

At a meeting between Mr. Bravery and Mrs. Langdon, it was suggested that she should see Oscar Deutsch to discuss the matter. Victor Bravery promised that if Mrs. Langdon could persuade Deutsch not to proceed with his Odeon Seaford scheme, he would purchase the site and build a brand new cinema for her to lease.

At that time the site of the new Ritz was some way from the commercial centre of the town, and had been in recent years the town’s pound where any stray cattle were herded. It was strange that the Braverys had overlooked this plot of land in the town, for they were opportunists who bought and sold building plots all over Seaford, but they probably dismissed the Ritz site as of no retail value.

Mrs. Langdon did visit Oscar Deutsch in London, and pointed out that it was hardly fair trading, in her opinion, to sell the lease of one cinema, the Empire, to her late husband and herself, and then build a brand new cinema in direct opposition! Surprisingly Deutsch agreed, and explained that with his programme of new Odeons gathering momentum, his agents were exercising options on sites all over the country, and that he had overlooked the position at Seaford. Under the circumstances he was quite prepared not to proceed with the proposed Odeon at Seaford.

True to his word Mr. Deutsch took down the hording regarding the possible opening of an Odeon cinema for Seaford. Mr. Bravery, in turn, purchased the plot of land and put plans in place for the building a new cinema in Seaford.

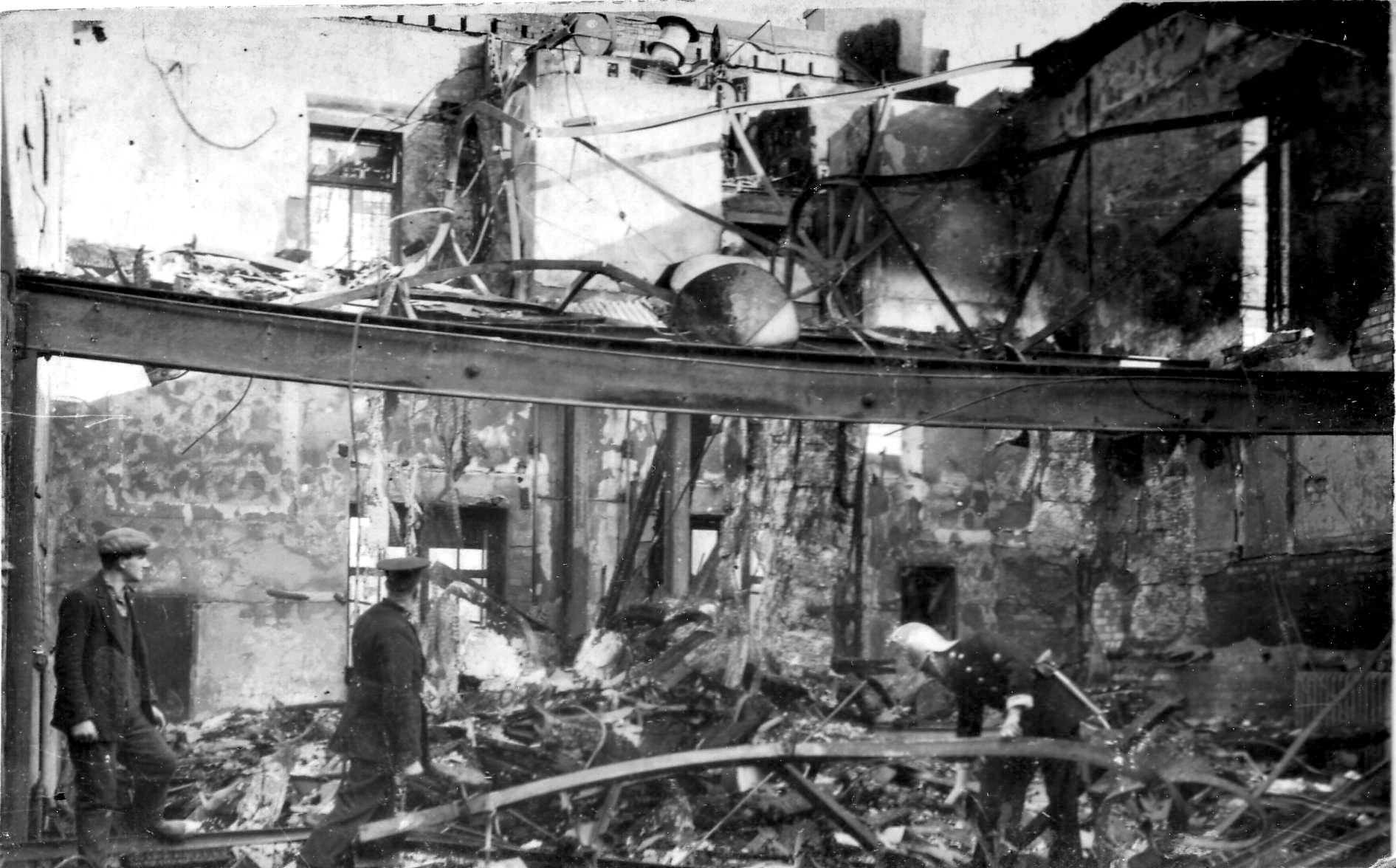

The Empire continued entertaining Seafordians even after the Ritz was completed, both cinema’s being managed by Mrs. Langdon and her daughter. It was debatable whether a small town like Seaford could accommodate two cinemas, but that debate ended one fateful night in 1939, when the Empire caught fire and a local fireman lost his life.

THE EMPIRE CATCHES FIRE

On Tuesday evening, February 28th 1939 there were two feature films showing at the Empire– The Port of Seven Seas, starring Wallace Beery and Walking Down Broadway.

After the second film the customers left, and the main electric switch near the front doors was turned off, the premises locked, and the staff went home.

One of the usherettes employed at the Empire, Miss Joan Coffen walked the short distance to her home in 9, Croft Lane.

At 1am. on the Wednesday morning, Joan’s mother, Mrs. Coffen looked out of her bedroom window and saw what she described as a flicker of light inside the lavatory window of the cinema It was almost like a piece of paper flickering to and fro, she said, and then, thinking that it was not worth bothering about, she returned to bed. Mrs. Coffen did not enjoy very good health, and three-quarters of an hour later she got up and looked out of the window again.

This time there was no mistaking the fact that the cinema was alight for the flames were quite pronounced and were licking round the inside of the same window. She promptly called her daughter, who at once partly dressed and ran round into Sutton Park Road and rang the fire alarm, a distance of about 150 yards from her house.The call was received at 1.50am, and the Seaford Fire Brigade were on site within eight minutes.

Chief Officer John Henry Reeves stated: “Directly we arrived we could see that the outbreak had started in the vicinity of the boiler room behind the stage and the flames had already got a good hold. They had already reached the roof at the rear of the building, and we were hampered by the fact that a very strong wind was blowing straight from the sea and therefore fanning the flames towards the centre of the building. In as short a time as possible we connected up fifteen 50-ft. lengths of hose and started to play water on the building and on the properties on its left and right.

We could see when the flames got such a hold that the interior of the building became a raging furnace, that the only thing to do to save the outer walls from falling was to play water on to the steel girders which ran from one side of the cinema.

At 2.30am Chief Officer Reeves soon realised that the assistance of the Newhaven brigade was needed and they in turn arrived shortly afterwards. Under Chief Officer Knight, they arrived in a very short time and, like the Seaford Brigade, set about their task in a workmanlike manner. They ran out another five 50-ft lengths of hose from hydrants and soon cascades of water were concentrated on the flames from all directions.

(John Henry Reeves. (Seaford Museum)

THE ACCIDENT.

The fire escape ladder was first erected and placed sideways to the front of the burning building. At that time it was about 40-ft. high and the two side props were put in position. Fireman Stanley Brown of 39, Stafford Road, heard the Chief Officer ask for volunteers to help, and four men, including Mr. Desmond White of the Belmont Café, came forward, and they stood at the foot of the escape to try and prevent the swaying.

Mr. Fred Mace an experienced volunteer fireman of 20 years was to climb the ladder and hose the flames from the top. Mr. Brown followed Mr. Mace up the ladder, and assisted to secure the hose. The wind was so strong it was hard for Mr. Brown to hold on to the escape ladder, and the pressure of the wind at the top, where Mr. Mace was hosing the flames, would have been enormous, but Mr. Brown’s duty was over. As soon as he was satisfied that the hose was secure and safe, Mr. Brown decended.

A little time afterwards the position of the escape was changed slightly and the four men continued to try and steady the bottom. At around 3.30am the escape ladder seemed to get sideways to the wind. The four men were not as strong as the wind, and with Mr. Mace at the top of the ladder, the escape crashed to the ground. Mr. Fred Mace was taken to Brighton Hospital where he unfortunately died from his injuries.

(The escape ladder. (Seaford Times/Sheila Green)

(Firefighting. (Seaford Times)

(The day after. (Sussex Express)

(Seaford Museum)

THE FUNERAL.

The funeral of Mr. Fred Mace took place on 4th March, and most of the townsfolk turned out to pay their respects as the cortege wended its way to St. Leonards Church where the service was held. The church was overflowing with Mr. Mace’s family and close friends, the Seaford Fire brigade consisting of Chief Officer Reeves, First Officer Harris, Second Officer L. Squibb. Firemen:- Charlie Mace, (brother of the deceased) Stanley Brown, D. Billings, Arthur Green, Carter, Edwards, Driver, A. Richardson and Grey. Also representatives of the Newhaven and Worthing fire brigades, the Seaford and Newhaven Auxiliary Fire Brigades and the St. John Ambulance. Also members of the Seaford Urban District Council, and Seaford branch of the British Legion.

The church may have been overflowing, but it was the hundreds of Seafordians that lined the streets as the cortege left the church and slowly drove through the town towards the Seaford cemetery that displayed the respect and the popularity of Mr. Mace. On each side and to the rear of the fire engine carrying the coffin of Mr. Mace marched members of the Seaford, Newhaven and Worthing fire brigades and their respective Auxiliary fire brigades.

The coffin was covered in the Union Jack, and carried on a brand new fire engine that, ironically, was delivered later on the day of the tragic Empire cinema fire. Every other square inch of space on the engine was covered with floral tributes, around 70 in all.

( Cortege leaving St. Leonards Church. (Seaford Times)

(Cortege in Clinton Place. (Seaford Times)

( Fred Mace (Seaford Museum)

(In memory of Fred Mace. (Seaford Museum)

CHAPTER THREE

THE RISE & FALL OF THE RITZ

The Ritz Seaford, was built and opened in 1936. The foundation stones were laid on 6th February 1936 by Tom Godfrey J. P. and C. J. Bravery and the cinema was opened to the public just five months later — an incredibly short period of time considering the size of the theatre, which was flanked with eleven modern shops and offices above, the elevations of which corresponded with the main building, on the frontages to Dane and Pelham Roads.

The Ritz opened on a Saturday night, 18th July 1936, at 8.15pm and the ceremony was performed by Lady Elsie Shiffner, Q. B.E., J. P., who lived at Offham near Lewes. Many other local dignitaries were present, together with the promoters, the architect, and Dorothy Boyd, a stage and screen star of the period.

The main feature that night was ‘The Amateur Gentleman’ starring Douglas Fairbanks Jr., Elissa Landi and Gordon Harker. It was supported by the Gaumont British News and a Walt Disney Technicolored cartoon On Ice, which featured Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, Goofy and Pluto in the days before these characters had separate cartoons to themselves. On stage were the Hastorians Band, Diana, and Tony Mockford, billed as the wonder boy pianist. On opening night, all available seats were priced at two shillings (10p).

(Picture House)

GENERAL DESIGN

The Ritz was promoted by the Seaford Empire Company of which Victor Bravery was merely a director, handling the business side of the affairs for his father, Charles J. Bravery. As far as can be seen, plans for the Odeon Seaford were not sufficiently advanced for any drawings to have been made, therefore the Ritz bore no resemblance to an Odeon.

How it was that architect Major W. J. King of 16/17 Jermyn Street, London SW1,came to design the Ritz at Seaford is a mystery. W. J. King specialised in acquiring sites, building cinemas on them designed by himself, and then leasing them off to one of the major circuits as they were completed. Seaford was most certainly not a piece of speculative building. Most other W. J. King cinemas were built in Middlesex and a curious spin off from this was evident at Seaford. Licensing authorities in Middlesex insisted the words “Way Out ” be used while every other authority stipulated “Exit”. At Seaford all the exits follow the Middlesex pattern of “Way Out”

The builders were Leighton (Contractors) Ltd., 62 Oxford Street, London, but some of the work was sub-contracted to local Seaford companies. The Ritz was designed on modern lines. For the comfort of those to whom stairs are a burden, it was contrived to make the circle within nine steps of the ground level.

The auditorium provided potential accommodation for 1000 patrons — 700 in the stalls and 300 in the circle. However, the original seating capacity was never more than 860, as Mrs. Langdon and Mr. Bravery insisted on wide spacing between rows.

The tasteful decoration was in Dubarry rose with pleasantly contrasted furnishings in eau-de-nil.

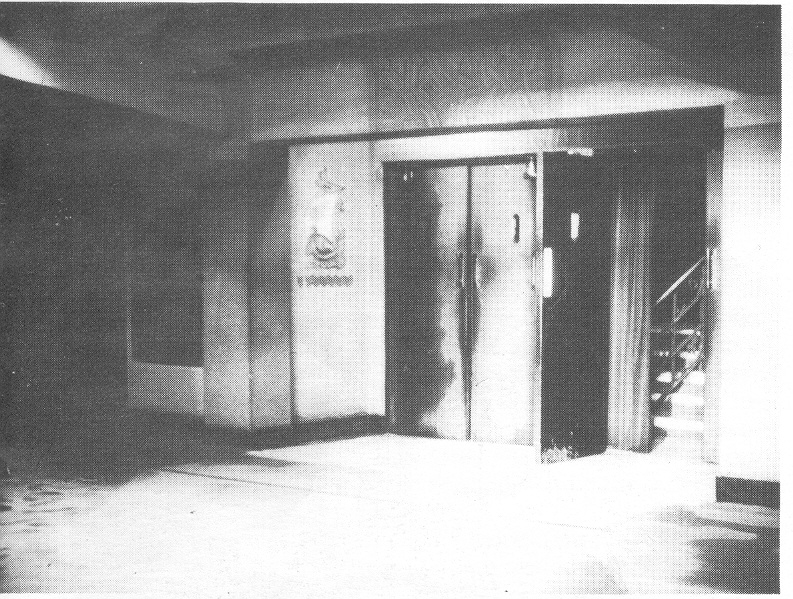

THE EXTERIOR

The Ritz was a lavish building situated across a corner site, at the junction of Dane and Pelham Roads. Holidaymakers arriving by train at Seaford Station could not fail to both pass and notice the Ritz on their way to the seafront. Motorists too would most probably pass the entrance to the Ritz on their way to the sea from the town’s main shops. At the Ritz, drivers had the benefit of a large car park immediately behind the stage area of the theatre. There was a combined restaurant and dance hall over the entrance to the cinema with a separate entrance to the right hand side.

Shops, cinema entrance and restaurant made a perfectly integrated building that was a credit to the town in the days when South Coast seaside resorts vied with each other for popularity. The new entertainment centre of the Ritz Cinema was an amenity that helped Seaford to present itself as modern and up-to-the-minute, equally good for holidays or retirement.

(Photo Seaford Museum)

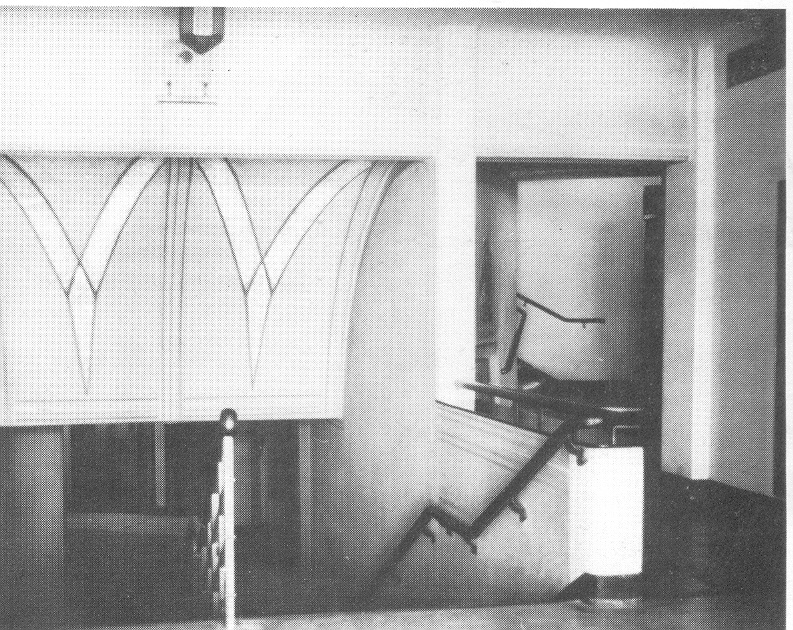

ENTRANCE AND FOYERS

Inside, the Ritz was exceptionally well equipped. A large ticket foyer with two identical pay-boxes in the left hand wall led to an inner foyer via three sets of double swing doors. The ticket foyer was furnished with an easel category board together with an easel frame for holding details of the items in the current newsreel. On the side walls were various display frames. In the glass panels above the sets of double doors leading to the inner foyer on both sides were the long display posters advertising forthcoming productions. These would gradually be moved forward, from inner foyer to outer foyer, until when the film they advertised was actually showing they would be pasted to the display frame that was over the outside doors to the theatre, on the street.

A ticket checker was always positioned by the left hand set of double doors, nearest to the pay-box. The admission ticket was torn, and patrons directed to either the stalls or circle. If it was a circle ticket, then there would be a further instruction as to whether to take the left hand or right hand entrance to the circle, depending on which side the usherettes were filling the auditorium.

On the left hand side of the inner foyer was a small cubicle that housed a public call-box telephone. This was later converted into a cigarette and confectionery kiosk. Facing this, on the opposite side wall, was a set of double doors that led to the restaurant above.

Immediately to the centre of the inner foyer, facing the patrons as they entered was a wide set of carpeted stairs that led downwards. This was the way to the stalls. On either side of the staircase were wide passageways that led to the circle. Bearing in mind that the Ritz was constructed on ground that slightly sloped away, the circle was more or less street level, and this was the reason patrons had to go down to the stalls.

(Photo Seaford Museum)

(Picture House)

Leading off the passages to the circle were toilets, gentlemen to the left and ladies to the right. The Ritz was very well equipped for toilets considering its reasonably modest size. There was the set for the circle, a set in the lower foyer, and a further set in the splay walls on either side of the proscenium. No expense was spared, even here. The men’s toilets were fully tiled in an attractive shade of green, and the ladies were pink. Some tiles had a design representing wave formations, or some other motif of the sea on them, and these were worked into the overall design. The sea feature was a recurring theme in the interior decorations of the Ritz.

After one descended the stairs leading to the stalls entrance, the area opened out into another large foyer. This was the space underneath the circle, for the Ritz did not have an overhanging balcony, but was built on the stadium principle so popular with designers in the south. The stalls foyer was probably quite a problem for the architect, who had this large area of space and very little use for it. The cinema already had a restaurant over the entrance hall, and the stalls foyer would not be en route to the auditorium for circle patrons.

Like the rest of the building, the foyer was close carpeted and furnished with the tubular chromium steel furniture so evocative of the mid-thirties. Doors on each side led to passageways with emergency exits at each end and toilets halfway along. The battery room was also along here.

(Picture House)

The auditorium was not built between the two sets of shops flanking the building, but was parallel to the Dane Road frontage.

To gain admission to the auditorium there was a slight change of direction, and the steps leading down to the stalls foyer were across a corner. The two sets of double doors that led to the stalls were in the centre of the foyer. Immediately in front of the patron as he reached the bottom of the steps, before turning slightly left to approach the stalls doors, there was a huge Coltman display easel with a large “R” at the top, and the words “The Ritz presents” below. This presented stills from the next programme. As in the entrance foyer, other walls had more Coltman still boards on them, and mirrors.

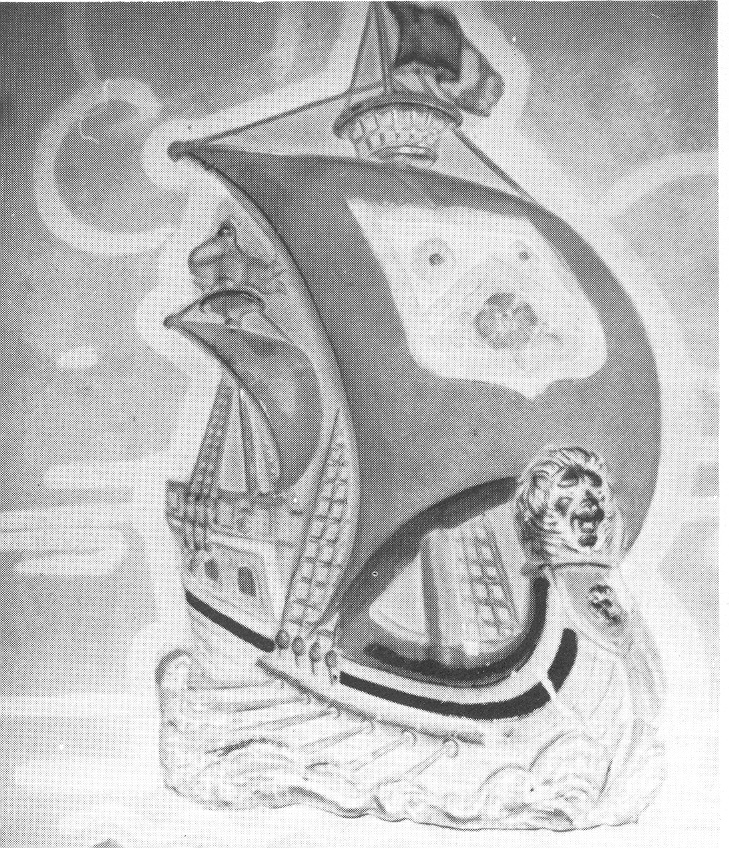

From the level of the stalls foyer, the auditorium was four steps up. In the side walls in front of the auditorium doors were moulded plaster panels of sailing ships. These were beautiful pieces of work, and further evidence of the architect’s wish to identify the theatre with the sea. Similar but not identical panels were to be found in other parts of the cinema.

(Picture House)

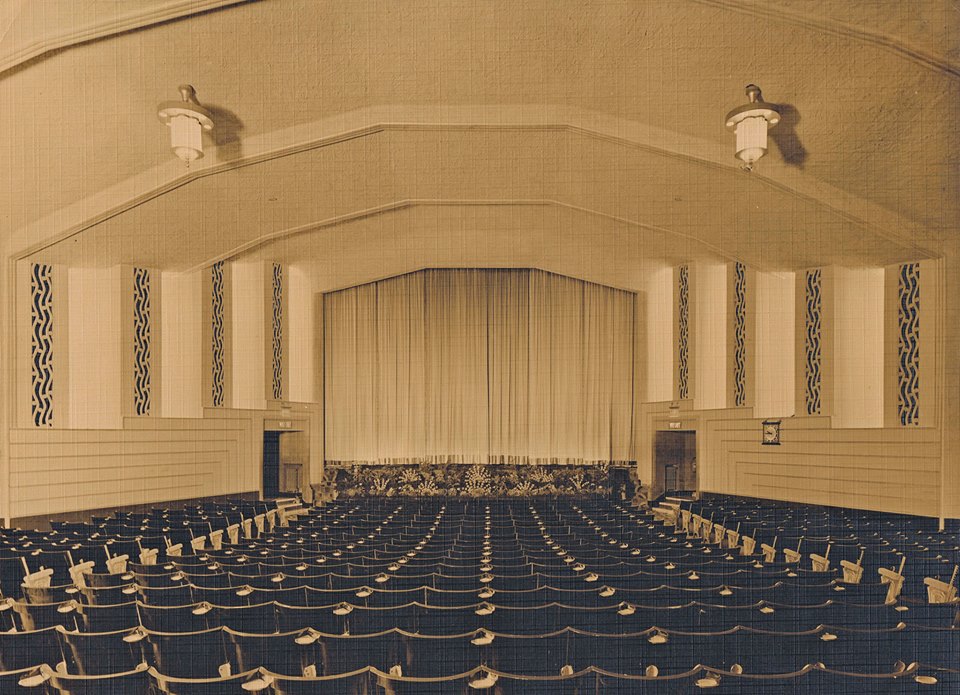

THE AUDITORIUM

The auditorium was wide, long, spacious and airy, although the ceiling was not all that high. In common with many other of Major King’s cinemas, the proscenium arch was shaped in a distinctive way. Instead of it being straight, or even curved across, at the top, the width was divided into three, and the two side segments sloped downwards. The suspended ceiling of the theatre followed this pattern. Although the centre of the ceiling was high, by the time it reached the side walls the height had been considerably reduced. This helped to make the cinema more intimate, and reduced the heating bills in the winter!

The auditorium was 133ft wide at the maximum point, and this tapered somewhat severely to 45ft at the proscenium opening.

The splay walls on either side held both the ventilation ducts and four recessed sections that were part of the lighting scheme. These were lit by concealed bulbs. Overhead were six large chandeliers of modern design, sympathetic to the atmosphere of the rest of the building.

Seating in both stalls and circle was in three blocks with two gangways. The seats were in rows of different colours. One row was rose pink, and the next eau-de-nil green. Decoration on the walls downstairs was quite plain, but in the circle the motif of the sea was continued, with silver and green wave tips. This looked quite attractive.

(Seaford Museum)

The auditorium chandeliers housed a great many bulbs. There was one in the base of the fitting and at least ten in the main body. Around the rim were another eight, and these were completely decorative. Very early in the life of the Ritz the chandeliers were de-lamped and just one bulb was left working. To make sure that no-one sneaked the lamps back, the cables leading to the other bulb holders were snipped! During the war, the chandeliers were taken down and stored, for fear of injury in the event of an air raid. Over the circle they were temporarily replaced by a non-matching pair of ordinary lounge standard-lamp shades, and stalls patrons had to make do with the lighting from the wall recesses.

Economy was put into practice with the splay wall lighting, too. Here just one bulb was laid across the base of each recess, and a modern fret-work design in metal was fitted to prevent the lamp from being seen. It was not until the management of the cinema changed in the 1970s that the full splay lighting was used. The chandelier’s bulbs were never replaced.

(Picture House)

MAXIMUM DEMAND METER

The reason for economy in the use of electricity was the dreaded ‘maximum demand meter’. In those days, local electricity companies in Sussex, and probably elsewhere, charged for electricity not only on the amount of the electric current consumed, but also according to the maximum number of kilowatts used at any one time. The meter was set to zero after each reading and it moved up a degree as a kilowatt was added to the load.

The largest demand would probably come at the start of the last house, when both projection arcs might be fired, house and stage lights were on, foyers, passages and entrance hall illuminated, together with possible outside floodlighting and neon signs. The standing charge, calculated via the maximum demand, was very expensive. Footlights were often wired in circuits of 1,000 watts, and if two colours were accidentally put up at once, the maximum demand would move up, even if the lights had only been illuminated for a few seconds, and the next bill would show a £20 or so increase. Cinema proprietors kept a very strict eye on the M.D. meter and made whatever reductions they could in demand.

THE STAGE

The stage was 36ft deep. In pre-CinemaScope days there were two sets of electrically operated tabs. The main house tabs were plain satin with a shiny band at the bottom that roughly followed the design of the proscenium arch. Behind were several sets of legs of peach colour, with festoon borders. The screen tabs were a rigid edge, side opening festoon.*

The screen was on a frame away from the rear wall, and the black serge masking had square corners. The Ritz never had the rounded corners so popular in cinemas of the mid-Thirties. Effective stage lighting was provided by two battens and by floats. The number one batten was just behind the main tabs, and number two was in front of the festoons. The footlights were slightly lower than the stage floor and there was a gap between the edge of the stage and the lights. Later on this gap was boarded over with the result that a shadow was cast on the lower part of the festoon curtain and the pleasing effect on the curtain lit from top and bottom in contrasting colours was never fully realised.

The single horn speaker of the B.T.H. sound was in the space between the screen and rear wall. To help with the acoustics, W.J. King specified a plaster finish to the auditorium that was rather like pebble-dash and he would not agree that acoustic tiles were necessary. There were criticisms of the sound at Seaford, but history has judged that B.T.H. was not the best sound system.

*Rigid edge means that the leading edge of each curtain was fixed top and bottom to the hauling cable which, besides passing through the curtain track, also by means of pulleys passed along the stage at the foot of the curtains. Unless side opening festoons were fixed top and bottom, the sheer weight of the material in the festoon made the curtain taper. Rigid-edged festoon curtains were expensive to install and more prone to go wrong, and this is the reason why some interior designers specified a side opening festoon that had a panel of non-festooned material on the leading edge. This did not require the extra cable and pulley work.

PROJECTION

The projection suite was at the rear of the auditorium, and due to the design of the cinema the throw of 156ft was almost level. Like the rest of the building, the projection area too was on a lavish scale. Entrance to the projection suite was from the right hand corridor between inner foyer and circle. There was a sizable re-wind room, a rectifier room, a dimmer bank room, and a projection staff toilet. The projection room itself had a highly polished teak floor and was equipped with two Kalee 12 projectors. This model had dials that showed the speed at which the film was passing through them. The arcs were Vulcans and the sound system was British Thomson-Houston. There was also a spotlight and a separate slide projector. The switchboard and the lighting equipment were supplied by F. H. Pride Ltd.

RESTAURANT

The restaurant and dance hall was above the main entrance to the cinema. The carpet and the furniture was of the same design as that in the rest of the building, and the walls, plaster work and mouldings had that definite cinema feel about them, just as the foyer and auditorium had below.

Mrs. Langdon’s lease included the restaurant, and it remained open until after the war. The restaurant was used for other functions— indeed Mrs. Langdon’s daughter held her wedding reception there. In the early 1950s. the Seaford and District Amateur Operatic Society rented the premises for rehearsal rooms for a while, and later it became a night club called The Crow’s Nest. For long periods, however, it was disused.

CHANGES IN MANAGEMENT

For the major part of its lifetime, the policy of the Ritz was in the hands of Mrs Langdon and her daughter. Mrs. Langdon had retained a pleasant business relationship with Oscar Deutsch, and she took over the Odeon Lancing during the war as well as the Deutsch-managed Rothbury at Portslade from the builders, Mr. and Mrs. Middleton, who had got into a hopeless muddle when Oscar Deutsch withdrew.

In 1958 she took over the Abbey Cinema at Battle.

At Seaford her admission prices were always high. Whereas in other cinemas the stalls were priced at 1/- and 1/9, Mrs. Langdon’s prices were 1/-. 1/9 and 2/6. The circle was 2/9 and 3/6. During weekdays the theatre opened at 5 o’clock, on Sundays at 8pm. The Wednesday and Saturday matinees, at 2.30 with reduced prices, were popular with the retired patrons, and continued until June Howard resigned.

Mrs. Langdon was very careful about the product she booked as she catered for what was called the carriage trade. Newhaven was only four miles distant, and for most of the time both towns crossbarred each other.

Newhaven had first run on all Paramount and Warner product, but Seaford had the rest.

Very occasionally 20th Century-Fox films played concurrently. On average, rental for films was 40%.

Gaumont-British News was shown when the cinema opened in 1936 and this continued until 1947 when the reel was changed to Movietone and then British Paramount News. Projection standards were excellent. Fade-ins on the Censors’ certificates, where printed on the film, were always screened and the films were shown in their entirety, right to the end of the cast. They were never ‘slipped’ even at the last performance. Changeovers were uniformly good, with no dialogue clipped.

For a medium-sized South Coast town, the Ritz was an ambitious project. The Empire had burnt down in 1939 and was never restored, so the Ritz served the town on its own for forty years.

When Mrs. Langdon died in 1961 her lease died with her, and no other lease on the cinema was ever issued. Victor Bravery died two years after Mrs. Langdon, and Mrs. Langdon’s daughter, Mrs. June Howard, was invited to run the cinema as an employee of the Seaford Empire company.

The Ritz closed in June 1970, mainly because it was in such a dreadful condition. There was no proper heating, the seats were in need of repair, and it was dirty. Mrs. Howard reports: “It was just not worth running. The audiences were so small and no wonder! I wouldn’t have paid to go there. No money had been spent on the place almost since it was built.”

The staff, most of which had been there since wartime days, including the projectionist, Percy Brunsdon, who had come from the old Empire, resigned en bloc.

The Ritz would have remained shut had the Seaford Empire company not discovered that no insurance could be obtained unless the place was occupied. Hence there was a desperate search for a tenant.

The Ritz was re-opened on July 1st by Roy Markwick of Uckfield Picture House, who traded under the name of Hallmark Cinemas. Mr. Markwick was charged a rent of £900 per annum, and he was responsible for all insurances. By this time, business had declined to such an extent that the Seaford Empire company had applied to the Old Seaford Urban District Council for planning permission to redevelop the entire Ritz site into shops and flats. But in 1970 the bottom had fallen out of the property market and, although planning permission was granted, there was no money to finance the redevelopment.

Roy Markwick replaced the original B.T.H. sound with R.C.A. resprayed the screen and fitted Peerless Arcs. Later he threw the old Kalee projectors into the rectifier room and installed some second-hand Westars.

The introduction of Value Added Tax brought about Mr. Markwick’s departure from Seaford. He wrote to the Seaford Empire company giving notice that he would vacate the Ritz on 30th April 1974. The people of Seaford just did not care about their cinema, he said. They would not attend whatever film he put on.

In August 1974, the late Myles Byrne agreed to re-open the cinema, so long as he could have it for no rent at all. As Roy Markwick had removed projectors and sound system to his planned twin at Uckfield, Myles Byrne had to start from scratch.

He acquired some ex-government Kalee 11 machines that were brand new, found some Nevillectric rectifiers, installed another set of RCA sound equipment, and opened up for business.

With the threat of possible redevelopment hanging over his head, or even whether he would be able to make the cinema pay, Myles Byrne did not redecorate either, apart from a quick colour wash to the main entrance.

In the summer of 1977, Myles Byrne was persuaded by one Bill Byrne to go into partnership and present a summer ice show at the Ritz called The Jubilee Ice Show of 1977. It opened on Monday July 25th and folded after just two weeks. It was dreadful. The ice pad was a tiny 27ft by 24ft, the total cast, both chorus and principals, numbered just twelve and the lighting was provided by nothing more than the old number one batten, hastily slung in front of the proscenium, over the front stalls where the ice pad had been constructed. The whole production was hopelessly under-financed.

It had been predicted that the ice show would run for six weeks, but only half a dozen or so members of the public supported the daily 2.30 and 8.00pm performances and the summer spectacular could not continue. On Monday August 8th films re-commenced.

In the autumn of 1979, the cinema was operated by Shirlmoss Ltd., and run by Stephan Wischausen, who operated a number of cinemas for a short while in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

But the writing was on the wall for the Ritz and it did not survive the winter of that year. The roof needed several thousand pounds spent on it, and the original electricity circuits were in urgent need of renewal.

In the original leasing agreement between Mr. Bravery and Mrs. Langdon, the lessee was responsible for the day-to-day running expenses of the theatre, but all the inside fixtures, furniture, equipment and decorations were the responsibility of the landlord.

The lease was a decoration and repair lease. Victor Bravery knew very well that

all decorations were his company’s responsibility, but it was like getting blood out of a stone to get him to do anything that would cost money. Rent for the cinema was fixed at 25% of the gross takings.

On the day that demolition commenced at Seaford, in March 1985, the Ritz was still painted in its original colours, in fact in its original paint! The Ritz Seaford must have been the only cinema that had never been redecorated in all its forty-nine years of operation. True, when it changed managements in the Seventies, the foyer was tickled up, and the outside was repainted after the war because of bomb damage to a building opposite.

A new Safeway store was opened at the end of July 1986 on the site of the old Ritz. This supermarket covers the entire area of the former cinema, shops and car park, and it is a reminder of the vast and ambitious project that the building of the Ritz complex was in its day.

(Mrs. Howard comments):

“The Ritz should never have been built. It was too large for the town, and Seaford was certainly not big enough to support two cinemas as it tried to do when both the Empire and the Ritz were in operation. If we had had the Empire, we should probably still be running it today.

Had not the sign for a new Odeon been erected, the Ritz would have not been built. It was a barn of a place, and very difficult to heat. There were no radiators in the auditorium. The heating consisted of hot air being blown through the grilles on either side of the proscenium. The cinema never did really well, even when it first opened, and although it was full during the war, the takings were well down as troops could always get in for 6d.(2 ½ p).”

(Seaford Times comment)

Had Mr. Bravery, a very wealthy man, obeyed the terms of the lease, a lease that he had agreed to with Mr. & Mrs. Langdon back in 1936, the Ritz might still be in use today in one form or another.

The Beginning.

The Ending