THE HISTORY OF THE FITZGERALD ALMSHOUSE, SEAFORD

Its Foundation, development and response to social change.

Reasearched and written by Charles A Grimble BSc. FCIoH (retd)

August 2019.

INTRODUCTION

Post-Reformation, the responsibility for assisting the poor in any English parish rested with the parish board, which had its roots in the established Church of England, as the all-encompassing body with recognised charitable aims. One obligation towards the ‘impotent poor’ under The Act for the Relief of the Poor 1601 was to provide almshouses or a poorhouse. Seaford already had one, in the form of the old Leper Hospital (in Blatchington Road), a foundation dating back to 1147AD when land and funds were gifted by Roger de Frexineto for this purpose. However, over the years this had deteriorated and it is now believed that the ruins of the Leper Hospital at Seaford were cleared in 1780 and Seaford parish workhouse was built on the site. In 1810 the inmates of the Seaford workhouse were moved to a larger facility in Eastbourne and the two cottages sold for private use. As a result of the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834, the relief arrangements for Seaford werefurther amended, by Seaford being formally merged with the Eastbourne Union in March 1835. Because of the significant agricultural community, the Eastbourne Guardians successfully petitioned Somerset House to be allowed to continue ‘outdoor relief’. This enabled aged paupers to be supported in their homes. The Seaford vicar, Rev James Carnegie,(vicar St Leonard’s 1824-1864) ensured that this support was given, as he was often the first port of call by disgruntled paupers, and he saw himself as ‘their natural guardian’. This meant that a handful of aged couples and individuals stayed in the parish. This avoided the particularly punitive treatment usually given to inmates of workhouses who were classified into able bodied; elderly; infirm; children, and then separated by gender. Families were thus divided within the workhouse. Because of the preference for ‘outdoor relief’, the able-bodied were supported in their homes. This meant that the residue- the elderly and infirm, were largely accommodated within the workhouse. It is in this environment that John Purcell Fitzgerald made his significant contribution.

John Purcell Fitzgerald (1803-1879)

Robert Bernard Martin describes him in relation to his siblings as “easily the most eccentric of a peculiar lot”(Martin, 1985, p. 30). This is a very poor summary of a man who, from his actions described in this paper, was of vision and integrity with a real heart for the poor in the community. Fisher describes him as “a highly eccentric and grossly fat lay preacher, and lived much at Castle Irwell on the Pendleton estate outside Manchester” (Fisher, 2009).

In January 1858, after his mother’s death. John jnr. took the surname Purcell-Fitzgerald. He married twice. His first wife, married in 1832, was Augusta Jane Lisle Phillipps, daughter of Charles March Phillipps of Garendon Hall. After her death in 1837, he married Hester Haddan in Lewishamin 1843. Hester died in 1888 at Boulge Hall, Suffolk. Gerald Charles Fitzgerald (1820–1879) and Maurice Noel Ryder Fitzgerald (1835–1877) were sons of the first marriage (Fisher, 2009). Both sons died before him, so the estate passed to Maurice’s son, Gerald Purcell Fitzgerald (1865-1946).

John Purcell Fitzgerald jnr. was a pupil of Benjamin Heath Malkin, headmaster at Bury St Edmunds Free School. He matriculated at Trinity College, Cambridge in 1822, graduating B.A. in 1826 and M.A. in 1829. The Cambridge Alumni Databasestates that when young he “had suffered from brain-fever which had had the effect of so weakening his sight, that it became impossible for him, as had been intended, to take Orders in the Church of England. In evangelical circles he was valued as an eloquent and earnest preacher, but eccentric. ‘John’, said his brother, ‘means well but he adopts extraordinary methods to attain his ends’. Martin comments that he “had been strange all his life, sufficiently so at Cambridge to warrant special attention for eccentricity“. He had a speech impediment, described as “a bad sissing or whistling … that alternated with a clicking of his teeth“. Nonetheless he took up preaching, and attracted audiences in the 1840s to hear his views on biblical prophecy. He was also a jurat of Seaford Town Council and was elected Bailiff for the town for one year commencing from 29 September 1852.

Although he had numerous family properties in Ireland and England, (John also inherited Boulge Hall from his mother in 1855), he continued to live in Seaford occasionally until 1858 and showed a remarkable commitment to the needs of the local community.

After 1858 he resided for much of his time at Castle Irwell. He had additions made to that house in 1861. He was recorded as living in Boulge Hall in 1868. John resided from 1870 at Little Island in County Waterford but moved back to Suffolk. On his birthday (June 29) he generally gave a substantial dinner to his pensioners. He last visited Seaford in May 1872 when he distributed clothing, flannel etc to all inmates of the almshouse addressing the men and women assembled in a very kindly way. When the town was inundated by the sea in 1875, he promptly threw open Millbergh-House for several weeks for the use of the poor washed out of their homes, refusing to be repaid the taxes from the Relief Committee (W.Banks & Turner, 1881). He died on 4 May 1879 at Boulge Hall, Suffolk, leaving an estate worth under £12,000 (£1.5m in today’s prices). He is buried in the family vault in Boulge Hall.

His first act of charity in Seaford was to plan and build a National School for 150 children, on a site of one quarter of an acre, (now 71 Steyne Road, Seaford, the 6th Form building of Seaford Head School) given by the Duke of Chichester. He laid the foundation stone in 1858 and it opened on 2 March 1859. Fitzgerald also founded a Lending Library for the Poor in Church Street, Seaford, and he contributed £100 towards the cost of restoring St Leonard’s Church in 1861-2.

The Purpose and administration of the Fitzgerald Almshouse

John Purcell Fitzgerald created the Fitzgerald Charity on 14 August 1858. The 12-page Deed of Foundation and Endowment was enrolled in the High Court of Chancery on 6 September 1858 placed before the Board of Charity Commissioners on 11 February 1862.

Its title states its purpose “for providing maintenance for aged and infirm labouring poor persons in the County of Sussex”. Its detailed text sets out clearly that this was his initiative specifically and it states that he “considered that under the present system of the laws for relieving the indigent and aged poor, those persons who are too old to labor (sic) for their own support receive but a scanty allowance out of the poor rates and considering moreover that the consequence of the inadequacy of this allowance to make them comfortable in their last years of life they are too often compelled to go to live in a Union or Poorhouse wherein according to the present general arrangements husbands and wives are practically separated for the remainder of their days”. He considered the inadequacy of the poor relief and the separation of spouses “to be contrary to the Letter of Christ’s Gospel and the teaching of his Church in all ages”. He stated such arrangements as the Trust made “shall be permanent and continue in force notwithstanding any change which may hereafter be made in the Laws for the better relief of the poor”. In answer to an early enquiry from Trustees, he clarified that he particularly targeted agricultural labourers. From the above declaration, it is clear that Fitzgerald was driven by a strong social conscience for his local community, which he had served, and was about to leave for his other estates. That social conscience was guided by his strong Christian faith, and was both a man of principle and also very practical in ensuring that his wishes were fulfilled, in a scheme with what we would call now, a highly sustainable project. It is interesting that though he envisaged the possibility that the law could change to effect his seminal principles, he wanted his scheme to both point the way forward, and continue beyond such possible changes. He envisaged that not only would the almshouses provide shelter, but also pay a small pension to each occupant whilst they remained there. In 1858 this was for men 4s 6d (22.5p) for women 3s 6d (17.5p) and couples 8s (40p). This lifted them out of poverty. These pensions were still being paid either in full (9s/45p), as in the case of Mr Thomas Funnell and his wife Sarah, or as a supplement to income in January 1917, as is clear from the Trustees minutes. The beneficiaries also had to have lived for the previous 10 years within a 9-mile radius of St Leonard’s church, with preference for those who had been brought up and laboured within that area. There was no preference for a particular denomination of Christian, which was unusual at that time. It seems also that from an early date, all residents received 5cwt of coal each Christmas until this was stopped in the 1970’s.

The Trust & Trustees.

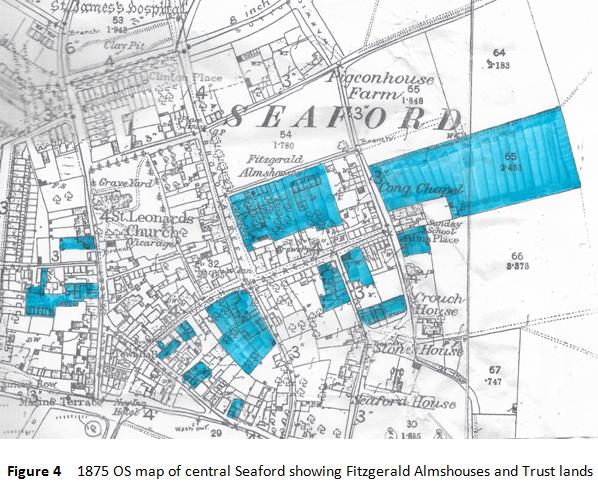

To meet the significant capital and revenue costs of such an undertaking, a significant property portfolio providing rental and investment income was required. To enable this, Fitzgerald transferred all the land in Seaford that his father bought, apart from the Millberg/Corsica Hall estate, and placed it in a Trust.

The institution was founded by 7 signatories including J.P. Fitzgerald, his son G.C.P. Fitzgerald, Rev. Carnegie (vicar of Seaford and Chairman of Trustees) and the Earl of Chichester and two local vicars, of Eastbourne and of Hailsham. The seventh person, John Meadows White (1799-1863) was an eminent Parliamentary solicitor who published works on Tithe Law reform, and the Poor Law Amendment Act.

It is clear that Fitzgerald intended the local large landowners and people of high status to continue to be aware of the needs of the poor by being Trustees- they had no excuse for not knowing! The Bailiff of the Seaford Corporation was also an ex-officio trustee to allow for further local accountability. It took some time from the adoption of the rules on 14 August 1858, to the laying of the foundation stone by J.P.Fitzgerald on 20th July 1864. During that time, beneficiaries were housed within the endowed portfolio.

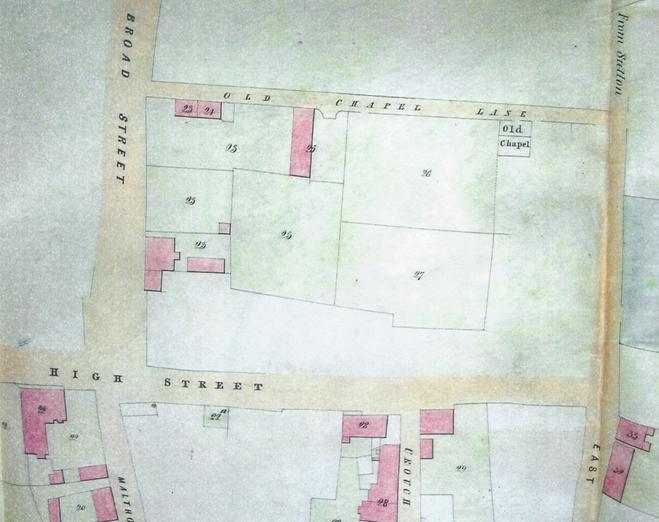

The 1864 building was constructed upon a greenfield site within the town, on a lane named Old Chapel Lane after the old chapel which could well still exist as the front part of Elm House (see Fig 5). Plots 26 and 27 in the schedule describe the sites as gardens and allotments. The other side of the lane was undeveloped fields. Plot 23 was the site of the old Hurdis House which had been destroyed in 1824. John Fitzgerald bought the site from a Mr Pindar shortly afterwards.

The original Almshouse contained 19 rooms which were arranged as 4x double rooms with 4 larders to the left of the tower viewed from Croft Lane, and 4 x double rooms with 4 sculleries to the right, and in the tower section, 1 double on the ground floor, a double and a bedsit on the first floor and 2 bedsits on the second floor, together with the luxury of a shared WC on the second floor (presumably because of the long trek to the latrines in the back allotments!).The building was capable of housing 13 households and 23 people.

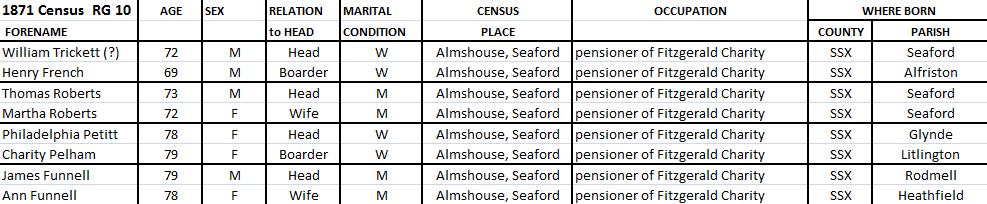

In the 1871 census there were 8 residents in 4 households. I would suggest that at this stage, the Almshouses were not completely full. The census does not identify empty property.

2 residents were widowers, 2 were widows, and 2 were married couples. All were pensioners aged between 69 and 79.

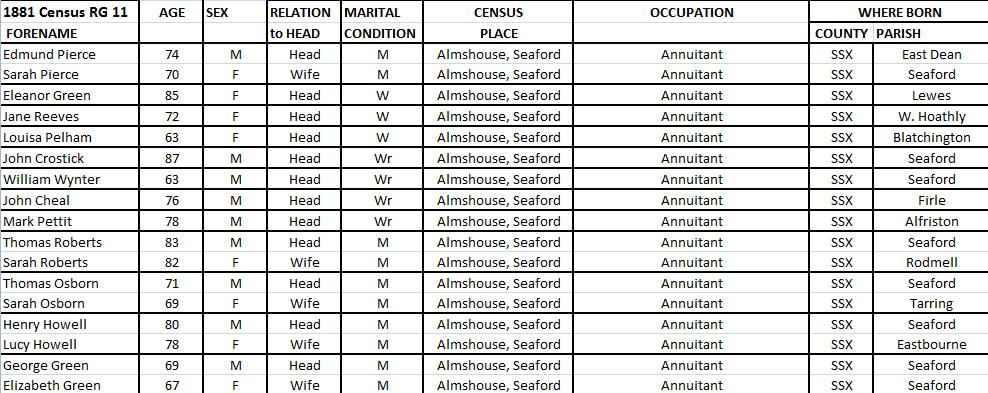

In the 1881 census, the almshouses have 17 occupants, within 12 households, of 5 couples, 3 widowers and 4 widows with an age range of 63 to 87.

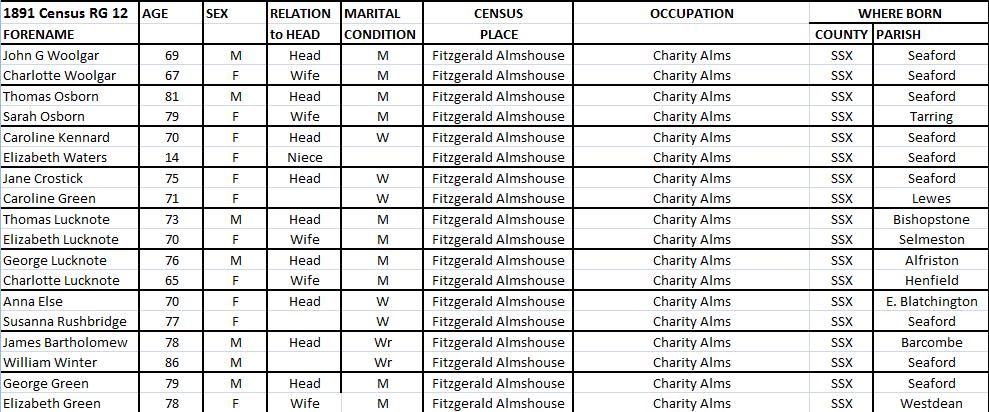

By the 1891 census, the lane now is called Cross Lane, and there are 18 residents in 9 households, 5 couples, and 4 shared households. For the first time one household is a cross-generational one, with a widow, Caroline Kenward aged 70, sharing with her 14 year old niece, Elizabeth Waters.

The new Fitzgerald Cottage

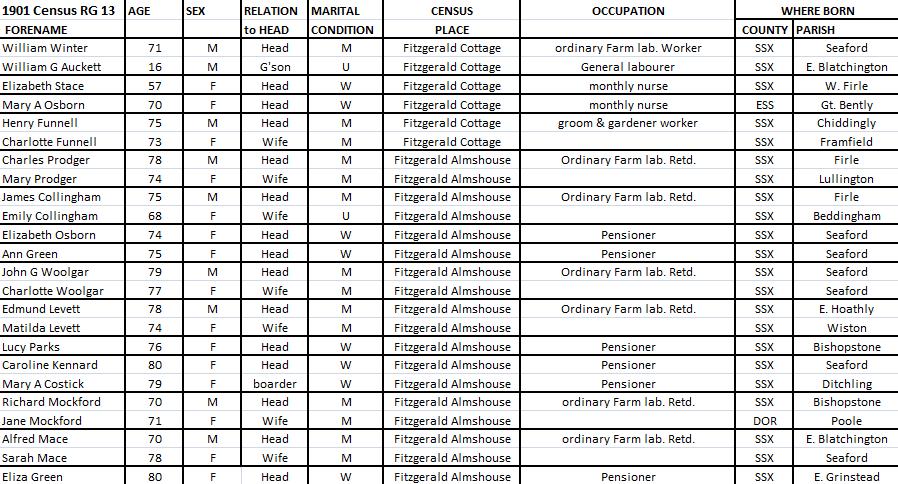

In 1893, a new free-standing block was added to the west side. This new detached building, initially called Fitzgerald Cottage, was home to the resident nurse and gardener, and additional residents in 4 households. This produced 8 x bedsitting flats, some of which could be combined to produce paired rooms for couples. This tallies with the 1901 census results showing 2 couples and 2 single person households for Fitzgerald Cottage. There are references in the Trust minutes to this new block being called the Women’s Block, because it was suitable for single women in the bedsits, and two women sharing a pair of rooms. It also showed an increase in the standard of accommodation, as each pair of rooms shared an inside scullery and there were paired WC’s on each floor in a two-storey purpose-built rear extension.

In the 1901 census, overall there were 18 residents, in 11 households. 6 households were couples, 5 households were single widows, with one widow sharing with a widowed boarder. The age range was between 68 and 80 years old.

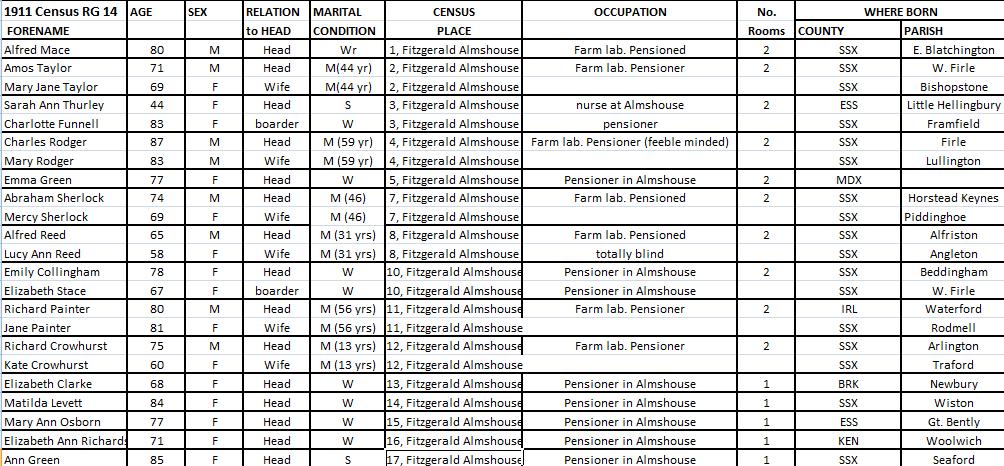

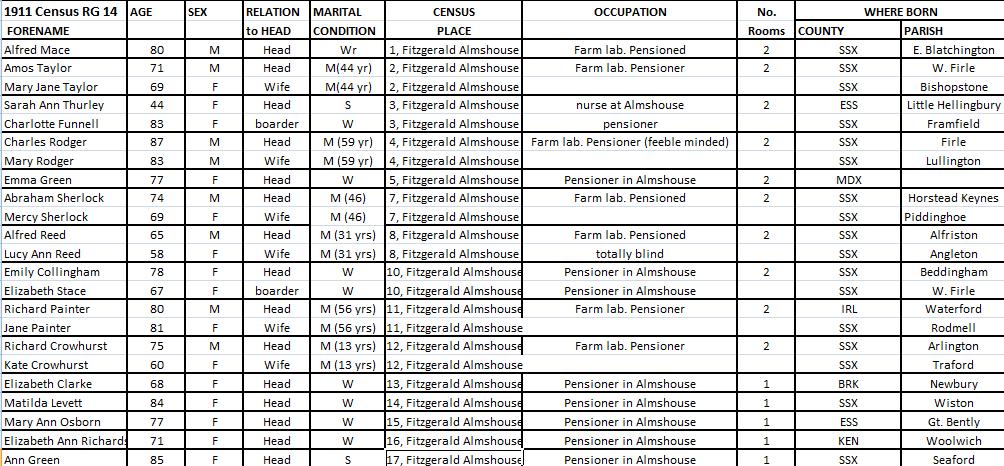

In 1906 a photo was taken of the rear of the almshouses, and featured Alfred Mace, the oldest resident at that time. Alfred was born in East Blatchington on 20 November 1830, baptised in St Peter’s on 1 August 1832 and died in 1915. He was a farm labourer.

OLD AGE PENSION ACT 1908

On 1 January 1909, as a result of the Old Age Pensions Act of 1908, the first state pensions were granted to around 500,000 people aged 70 or more. It was 5s (25p) a week and was paid in full to individuals aged 70 or more with an annual income of £21 a year or less reducing to nothing at an annual income of £31 a year. A higher pension of 7s 6d (62.5p) was paid to a married man. At the time only one in four people reached the age of 70 and life expectancy at that age was about 9 years. This had no impact on those residents who were over the age of 70, because of the terms of the original Deed of Foundation and Agreement. Thus, in the annual returns for the Charity for the year ending 25 March 1909 £330.16s 3d was paid out to pensioners. In the following year, £318 2s 0d was paid out and even at 25 March 1936, £316 6s 0d was paid out. However, it can be seen that these pensions were not indexed to inflation, and so gradually diminished in value.

The 1911 census gives us more information about the building, as well as details about its occupants. It records the occupants of 15 flats, (Flats 6, 9, 18-20 were empty). All consist of 2 rooms (the kitchen counts as a room) except flats 13-20, which are clearly bedsitting rooms. In 1911 there was a resident nurse, Miss Turley, who lived at No 3, and looked after the residents’ health. She left in early 1922.

Sale Of Land

On 30 July 1918, the Trustees started the process for a momentous decision that significantly changed their workload, the disposal of a significant part of the portfolio. Not all properties in the town portfolio were sold. The retained property was land, and those properties subject to long repairing leases, which offered a ground rent with little landlord responsibility. This move was essential because the repair obligations for the rented portfolio was increasingly a problem for Trustees and reduced the net income available for the Almshouse costs. This step had been authorised by the Charity Commissioners by letter dated 28 September 1918, and the sale took place at the Terminus Assembly Rooms on 28 November 1918. The properties were put together in 17 lots, and all sold, raising a total of £9,755, with legal and auction costs amounting to £375 8s 6d. This was promptly invested in stocks and shares, to yield an annual income to replace the lost income from rents and ground rents. In the year ending 25 March 1921, a reduced income of £488 5s 0d was earned. The value of stocks was given as £13,420 5s 5d. This deal in the short term seemed therefore to yield real capital benefits, although gross rental income in the last full year before the sale (1919) had been £682 12s 6d. That reduction in income was mitigated because of the reduction in expenditure on the disposed properties.

Adaptations of the Almshouse in the 1920’s& 30’s.

Regarding the almshouses, little changed in the 1920’s and 30’s apart from the provision in 1925 of 4 sheds for £55 between the old and new blocks ‘for the use of the Almshouse inmates’ and three 8ft long seats for the pensioners in 1927. A more significant change was first considered on 31 July 1928 when it was proposed that 2 first floor extensions be constructed on the south wall of the old block to provide additional WC’s for the residents. C. Morling, a local builder, was given the task of creating these closets for £268 and the work was completed in May 1929. A further 4 sheds were considered against the east wall of the old Almshouse and these were provided in 1930 when the red brick wall linking the old and the new blocks was also built to provide further privacy for the residents.

Individual properties in the portfolio began to be sold off piecemeal, such as Hurdis House, and the property in Crouch Lane leased to Mr Berry, the shoeing smith. In 1933 it was decided that the Tower would be more suitable for the resident nurse and so minor works were done before the new nurse arrived. Electric lighting was first installed in 1935 after an estimate of £42 was received from the Newhaven and Seaford Electric Lighting Company for wiring 21 pendants to sitting rooms and bedsitting rooms and 7 pendants in the passages.

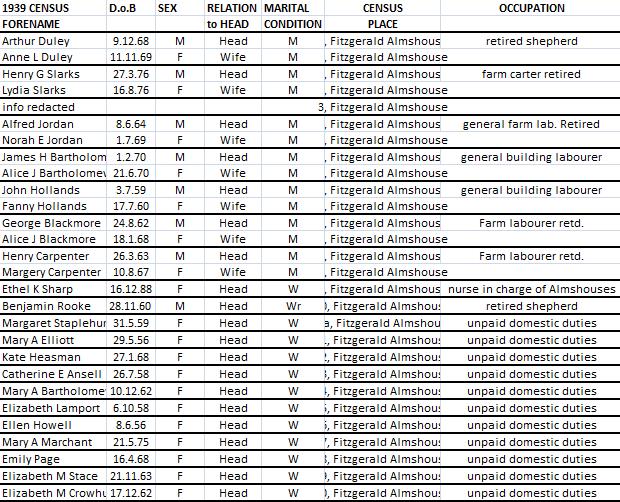

In the 1939 census, there are 21 addresses (1-20 cons + 10a). Mrs Ethel K. Sharpe is the nurse in charge, and lived in Flat 9. Flats 1,2,4-8 were occupied by married couples (3 was occupied by a single person whose name has been redacted). All the other flats are occupied by single people.

The Birth of Council Housing in Seaford

The Housing, Town Planning &c Act of 1919 (also known as the Addison Act), enabled central government to allow local authorities to provide ‘homes fit for heroes’ after the devastation of society caused by the Great War. This clearly was of interest to both the Trustees and also to Seaford UDC who were both quick off the mark in identifying development opportunities for new council housing. Thus, on 21 October 1919, the Trustees approved the application to the Charity Commissioners for the sale of a large field fronting onto East Street, adjacent to the Seaford Laundry to Seaford UDC (Plot 55 in the 1858 schedule and called Chapel Croft, now named Mercread Road). The sale for not less than £1,125 was approved by the Charity Commissioners on 6 May 1920, and Seaford UDC approved the terms on 16 August 1920 following sanction by the Ministry of Health. On 6 February 1921 the conveyance was approved by the Trustees and the sale was completed. However, the government realised that the subsidy provisions in the 1919 Act were too generous, and so, in 1923 and 1924, 2 Acts were passed to respond to both changes in political control of central government. The 1923 Housing etc Act,(called the Chamberlain Act) stopped local authorities receiving the subsidies, and passed them over to private developers, and the 1924 Housing (Financial Provisions) Act (the Wheatley Act) under the first Labour government restored local authorities as recipients of less generous subsidies. This remained in force after the Conservative Baldwin government took over in that same year. This legislation enabled Seaford UDC to build its first council estate to provide social housing as the post-WW1 version of support for those in housing need -true successors to John Purcell Fitzgerald’s vision.

The War Years

The outbreak of World War 2 had a significant impact on the Almshouses. At a Special meeting of Trustees on 12 September 1940, the Chair Rev. C H Maxwell stated that in view of the Evacuation Notice sent out by the Government, the first people to be evacuated were the residents. Those who wanted to were moved to a place where many could be housed together or that they could stay with friends, with arrangements to return ‘in due course’. It was also agreed that for the duration of their displacement, each married couple would continue to receive 7s (35p), single men 5s (25p) and single women 4s (20p) per week. In addition each couple would receive 10s (50p) and each single person 7s (35p) per week for lodgings. The nurse would remain on the premises as not all residents were moved away.

25 October 1942 was a memorable day for everyone. Enemy action had caused damage to the buildings but all the residents were safe, with two being taken to Newhaven Infirmary, and 10 others wishing to stay with friends until their rooms were restored. A special meeting held 3 days later stated that repairs were well in hand and by the following meeting on 15 December 1942, the first aid repairs were nearly completed. However, it was not until 2 September 1943 that an architect was appointed to report on the condition of the structure. He reported on 12 November 1943, and was instructed to do all that was necessary with the War Damage Commission. Eventually in 1944, a payment of £44 4s 8d was received from the War Damage Commission, so the damage was clearly not significant.

The Postwar years

The new communal bathroom.

The minutes of the Trustees on 25 April 1939 report that Miss V. Willett, a trustee, suggested that a communal bathroom be provided. It was resolved in July 1939 that this did not proceed, and shortly afterwards, wider global events meant the deferral of this idea until 7th November 1946, when the Trustees appointed the Trust’s architect, James A Avery-Fowler, of 15 Heathfield Road, Seaford to draw up proposals and on 18th March 1947, he applied for permission to build a side extension to the 1893 block. Surprisingly, he said in his application “This work is necessitated from the fact that no facilities exist at these buildings for the bathing of the many occupants”. Thus, over 80 years had passed before the occupants could have a wash in a plumbed-in bath. Seaford UDC clearly agreed the need and approved it on 16th May 1947. It was reported to be in use by ‘certain of the pensioners’ (not all)- clearly old habits die hard!!

On 23rd October 1952 the Trustees considered ending the granting of pensions to residents, with the view to increasing expenditure on the fabric of the buildings. Discussions took place with the Public Assistance Board, and after being told that the Board discounted the pension in their calculations of pension, the matter lay dormant until 16th September 1955 when it was resolved that new pensioners would not be eligible for the payment. On 25th August 1959, the Trustees finally agreed to cease this element of Fitzgerald’s scheme, having ensured that the National Assistance Board would make good the shortfall as a result of this major change. This was reported as implemented at the following Board on 17th December 1959. The financial impact was small; however, as I calculate the weekly value at that time would purchase a Series 3 Airfix kit! This small step, however, was one where John Purcell Fitzgerald’s original vision was pragmatically changed because government support for the elderly had stepped up to the mark, and improved the lot of the elderly.

The 1959 remodelling of some flats

The Trustees on 1st June 1956, considered plans produced by Messrs David Nye & Co. to carry out major improvements to the Almshouses. These plans were found to be unsatisfactory, and there was a desire to change architects, but on advice from the National Association of Almshouses, Trustees decided to try and get the plans amended to their satisfaction. Mr Nye attended a meeting of Trustees on 20th November 1956, agreed to adjust a couple of the 7 points raised by Trustees, but provided reasons for his proposals. That were accepted. The Trustees decided to apply for an Improvement Grant to help cover some of the cost of works.

Not all flats would be self-contained, and shared bathrooms would remain a feature. The electrical service would be improved to enable cooking by electricity, and every flat had a fireplace with a back boiler for hot water, except with shared bathrooms where a slot meter was provided to power the immersion heater. A local firm A.J Simmons & Son was successful with a tender of £6,655 17s 11d, all but £300 was for improvements. All of the cost of improvements would be covered by a 20-year repayment loan granted on 1st October 1959 under the 1936 Housing Act by Seaford UDC. The progress of the project was slow due to all the approvals required. Building costs rose, and so a revised loan was required under the new Housing Act 1957, and to add to this, A J Simmons was in the process of liquidation! After a great deal of consideration, negotiation and delay, it was reported to the Trustees meeting on 22nd August 1960 that C. Morling carried out the work for £7,655 5s 3d, reflecting additional work, the extra cost being met from the sale of some shares. All the 18 new flats were allocated to residents. It is not clear from the minutes where they went during the process. Although there are no floorplans showing these changes, it is clear that the front entrance of the 1893 block was closed up, as was the entrance to what was Flat 9 in the Tower, although both still retained their original framing features. The notes of the design discussions in 1956 show that the flat numbering was changed, because of the amalgamation of the bedsits in the 1893 block and the incorporation of the ground floor tower flat into the adjoining flat.

1960’s and the threat of demolition

The work, as indicated by the cost, did not pay for full refurbishment because, on 13th September 1966, the Trustees received a report from Mr F. H. Foster, architect to the Charity, which showed that “quite apart from a considerable amount of repair and renovation, the roof of the main block either side of the tower was in urgent need of repair”. The architect’s remedial work was estimated to cost £1,060 excluding potential additional costs for treating damp timbers, repairs/renewals of associated leadwork, eaves and gutters. Because of the age of the building “it was impossible to say just how much the final bill would amount to. Information supplied by the Clerk to the Council some year or so ago…indicated the life span of the Almshouses appeared to be fairly short owing to the possibility of a compulsory acquisition for shop re-development”.

The background to this astonishing statement was the publication by East Sussex County Council of the Town Map for Seaford and its submission to the Minister of Housing and Local Government in November 1965, followed by a local inquiry into objections in June 1966. The published document contains the remarkable statement ‘apart from St. Leonard’s church the central area contains no buildings of aesthetic quality when considered individually’ (L.S.Jay, 1966, p. 4). It noted ‘the buildings in the southern parts of the High Street and Church Street are in keeping with and help to create the intimate scale and domestic atmosphere brought about by the narrow widths of these streets’(L.S.Jay, 1966, p. 4). Given the later Grade II listing of the almshouses, this observation is clearly driven more by redevelopment objectives than by aesthetic considerations, and it condemned the almshouses to a frustrating period of indecision that lasted over a decade. In the light of this advice from ESCC the report proposed the demolition of all the Croft Lane properties including the Almshouses, 12-24 even Sutton Road, and the block of property on the east side of Broad Street from (but not including) Hurdis House south to what is now the Grumpy Chef. The proposal was to create a shopping precinct where the Almhouses would be replaced by a single storey shop unit, with rooftop parking. This radical solution was clearly too much for the residents of Seaford, and Shepway Parade and the Co-op are the only remnants of it. This proposal resulted in the Clerk being instructed to explore all options in order to establish a reasonable land value, to enable the Trustees to sell the site and purchase a plot for about 16 modern flats. At a meeting at the Council’s offices in September 1967, it was suggested that land at the Crouch plus a payment, be traded for the Almshouses site. It was clear that the cash element would not meet the estimate of £40,000 required ‘to rehabilitate’. Given the term used, it is not clear if the sum quoted was to provide for the 16 flats envisaged or not. In February 1968 the Trustees submitted an outline application to ESCC to demolish the Almshouses and develop the whole site for a shopping precinct with rear service area and overhead car parking. It was minuted that this strategy was aimed to ‘strengthen the Charity’s case and possibly precipitate matters with the Council and possibly clarify the value’. It was refused on 4th April 1968 on the grounds that ‘the proposal represents piecemeal development of an area which it is considered should only be re-developed on a comprehensive basis, and that the application was premature until the form of the future development of the adjoining sites is known’. This is interesting, as Shepway Parade on Broad Street, with shops and flats over, came on stream in 1969. This impasse dragged on for 3 years until on 7th April 1971 the clerk reported to the Trustees that ‘the National Association of Almshouses (NAA) was in contact with Seaford UDC….and at present there seemed to be a stalemate’. At this meeting the Clerk was requested ‘to ask the NAA if it would be possible under the Trust deed to close the present Almshouses sell the land and use the income of the Trust to provide amenities for retired people in the area’. This reflects the real dilemma of Trustees who were personally accountable for the assets, and at risk, because of a deteriorating property and vulnerable occupants. At this point, the number of Trustees reduced to 3, the Vicar and his wife and a Mr Edward Sales and his wife, advised by the Clerk.

A further application was submitted to Seaford UDC on 8th February 1973, to redevelop the sites as 40 flats with garages. That application was refused on 3rd May 1973, on the grounds that there was insufficient information to demonstrate the proposal can be developed in a satisfactory manner. To cover their options, the Trustees also simultaneously submitted a proposal for shops flats and offices with pedestrian access from Broad Street. That was withdrawn in the light of the May 1973 decision of Seaford UDC. As there is no discussion amongst the Trustees about what would be done if they were granted approval, I suspect it was an attempt to settle the land value in the negotiations of a land swap as envisaged by the discussions in 1967. Meetings of Trustees took place once a year in 1972, 1973, none in 1974, with the next one taking place on 11th July 1975. A key meeting took place on 4th February 1975 when the Chairman of the Trustees and the Clerk met with five councillors and seven advisors where the only agreed decision was that the Chief Environmental Health Officer would inspect the premises. No record of the outcome of that decision is recorded. This was clearly a low time for the Trust.

A new approach – enter the Housing Corporation

No further meeting of Trustees took place until 21st September 1977 where the Clerk presented a proposal to register the Trust as a Housing Association, governed by the Housing Corporation. At that meeting, proposals were also presented to reconfigure the Almshouses to create nine one-person bedsit flats, three two-person one-bedroom flats, and a four-person warden’s flat. A decision was made in view of the condition of the property and the Trust’s finances, that no new lettings be made. The national background to this uncertainty as to how to proceed was that the Housing Act 1974, created the Housing Corporation and also signalled a change from comprehensive redevelopment and demolition towards rehabilitation through Housing Action Areas and General Improvement Areas. Coupled with this national move, the Almshouses in 1976 had been included in an extension of the original Conservation Area that was created in 1969.The following year, at the first meeting of the Trustees on 9th June 1978 was told the Housing Corporation had no funds, and so that line of enquiry was closed.

On 13th December 1978 a new vicar, Rev. Michael Thompson became Chairman of Trustees and this coincided with a new period of significant activity, which although tortuous, involving Lewes DC, The Housing Corporation, The NAA and the Trustees, was ultimately very productive, ushering a new era, and some changes to the way the Charity related to its supporters. With Lewes DC providing temporary housing during the reconstruction phase, the Trustees appointed Oxley and Bennett Ltd of Newhaven as contractor, to designs produced by Mr Morling of Messrs Hubbard Ford. Planning approval was sought in July 1980. The Lewes DC website does not have record of this and so I cannot ascertain when approval was granted. It is a pre-requisite of Housing Corporation funding that planning permission is required and so I suspect the absence of an entry is either an administrative oversight when the planning records of Lewes DC were digitised, or because almost all the work involved internal remodelling, permission was not required. In return for a Housing Corporation loan to fund the works, the Housing Corporation required a legal charge on the title, which was arranged in April 1981 and lasted for 30 years. It is now discharged and the title is clean.

There was another significant change required by the Housing Corporation, that altered John Purcell Fitzgerald’s original concept, and that was the introduction of residents paying for their accommodation for the first time. As Residents of an almshouse, they did not pay a rent, but the equivalent sum to the then current Fair Rent was levied on the residents as a maintenance charge. The charge also covered the cost of heating the rooms, and providing hot water. This arrangement was authorised by the Charity Commissioners and sealed on 23th January 1980.

Because of alterations to the specification, the tender price increased, causing last-minute adjustments to the specification, enabling a contract to be signed with Oxley and Bennett Ltd for £91,514 on 14th August 1981, with work starting on 5th October 1981 and completion date of 16th July 1982. As the Trustees were also accountable to the Housing Corporation because of their acceptance of public funding, changes were needed in the way the business was run, requiring 4 meetings a year. These changes in the obligations of the residents led Rev Thompson to propose re-naming the Fitzgerald Almshouse to ‘Fitzgerald House’. It was proposed also that a paid warden be appointed. Mrs Joan Trumble was duly appointed after competitive interviews. She was succeeded on 1st July 1984 by Miss Sally Bawden. Despite significant expenditure, the cost reduction exercise that had been undertaken to keep the scheme within budget had resulted in tenants complaining early on about draughty windows and doors, and it is clear that the roof had only been repaired, not overhauled, as it started to show problem within a year of completion.

The listing of Fitzgerald House

The ill-conceived attempts in the mid 1960’s by ESCC I have described to demolish the buildings and redevelop the site in the 1960’s and 70’s, on 23rd March 1989, Nos 1-14 Fitzgerald House was granted Grade II listing (Source: Historic England ID1039983, English Heritage Legacy ID: 361755).

Despite the significant work that had been done in the 1980’s, there was an ongoing problem of the letability of the flats, particularly the bedsits. At any one time 3 or 4 of them were reported being empty for longer than would be expected.

The terms of the Trust Deed were altered to allow working people over 60 to be accommodated, but ultimately, Michael Blee was appointed to look at reconfiguring some of the flats after he submitted a report on 6th June 1991.

The estimate of £64,093 from V & J Baker was accepted on 24th January 1992 after a great deal of examination, and work started on 16th March 1992. That work produced the current layout with a mix of 7 bedsit flats, and 7 one-bedroom flats. This was sufficient until the last few years when major repairs were needed to keep the almshouses going, undertaken by local architect and surveyor, Michael Greve of G3 Architecture.

Conclusions

This was a singular, philanthropic initiative from a man whose father led a favoured but chequered path, marrying money, in an unhappy but fertile marriage, who bought a substantial portfolio of property in Seaford in order to justify being ‘the local candidate’ in the last throes of a corrupt political system being the last MP in the rotten borough of Seaford. Together, he and his highly individualistic and idealistic son, who, unlike him, was driven by a social conscience inspired by his overt Christian faith, used that portfolio to give the town 3 buildings that are important today- Corsica Hall, the first purpose built primary school, and Fitzgerald Almshouses. The latter has been, in my opinion, John Purcell Fitzgerald’s most lasting legacy, as it is still administered by a board of Trustees, following the principles first set out by him in 1858, and providing affordable housing for elderly people in the centre of town. In view of his parents’ unhappy marriage, and his being widowed once, his resolute aim, to ensure that married couples were not separated through the Poor Law provisions, is radical. The fact that he carried his plans out and they continued relatively unchanged for the 150 years since his death, despite the insensitive hand of local government in the 1960’s and 70’s, shows his care in selecting a sustainable vehicle for his project, even though it meant the loss of a substantial part of his inherited family fortune.

Both men are properly saluted in the town enriched by their two distinct needs, and their name is now recorded in Fitzgerald Road, close to Corsica Hall where they both lived.

The history of the Almshouses is, however, a microcosm of the history of social housing in the UK involving a private philanthropic initiative, the birth of Council housing, and the role of the Housing Corporation. Those changes over time to the detail of Fitzgerald’s original vision have reflected the social and legislative changes that have occurred, but the constant thread however has been the dogged determination of a succession of good-hearted local people willing to give of their time to be Trustees to ensue both residents and the property provide a much-needed contribution to society.